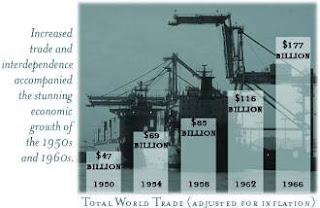

Increased trade and interdependence accompanied the stunning economic growth of the 1950s and 1960s:

- A typical 1960s U.S. telephone required 48 imported materials from 18 different countries.

- Foreign trade was a matter of economic survival for some nations. In 1960, Britain's imports and exports equaled 43% of its gross domestic product. West Germany's equaled 45%.

The rapid expansion of production and trade in the 1950s and 1960s required a constantly expanding supply of monetary reserves to increase total liquidity. Gold, the primary reserve asset, could not be mined fast enough to meet this demand. As a result, the U.S. dollar, and to a lesser extent, the British pound, were used as reserve assets.

- By the mid-1960s, a full third of the total market-economy reserves was held in U.S. dollars and British pounds, with the remainder in gold.

As Good as Gold

How does a national currency like the U.S. dollar become a reserve asset, adding to the world’s total liquidity?

- The United States runs a balance of payments deficit by spending more money in other countries (buying their products, investing in them, or giving them dollars) than they spend in the United States.

- The extra dollars are held by the countries’ central banks. The banks do not ask the United States to redeem them for gold or another currency. As long as foreign banks accept and hold dollars as if they were gold, the dollars act as reserves.

How long could the world rely on the United States and the United Kingdom to run balance of payments deficits and supply the necessary additional liquidity? Could the United States and the United Kingdom continue to create more dollars and pounds when their own reserves of gold were gradually declining?

The U.S. dollar fueled the growth of the world's economy, but at a price: inflation at home and reduced gold reserves.

"Too little liquidity could permit a crisis to develop in which most of the world would tend toward economic stagnation and would suffer from declining trade."

Pierre-Paul Schweitzer

Managing Director of the IMF,

November 16, 1964

Decolonization and Development

Uhuru (Freedom)

"Yesterday's dream is today's reality: we now have our Uhuru. We will guard Uhuru with all our might."

Jomo KenyattaThe colonies and dominions once controlled by European nations gained their independence starting in 1947, with India and Pakistan. In 1957, Ghana (formerly the Gold Coast) was the first African colony to achieve independence. Others in Africa and Asia followed rapidly over the next few decades.

Prime Minister of Kenya, 1964

The euphoria of independence quickly gave way to the sobering reality of the obstacles ahead. For many developing countries, independence brought civil war and economic chaos. Most developed "dual economies" - the majority of their people continued to live in poverty, while some urban, industrial areas achieved rapid economic growth.

"I am sure that every one of us will celebrate Independence Day with great joy. We are celebrating a victory. Yet it is essential that we remember even on that day that what we have won is the right to work for ourselves, the right to design and build our own future."

Julius K. Nyerere

President of Tanganyka (now Tanzania), 1962

The Foreign Exchange Famine

With independence came expectations of a better life. New governments promised modernization and prosperity. Leaders and citizens alike hoped to share in the economic success of the industrial Western world. To do this, they needed money, not just their own "soft" currencies, but foreign exchange in the form of internationally accepted "hard" currencies.

Where would the newly independent countries find the capital and additional liquidity needed to modernize and grow their economies?

The Dollar Glut

"Providing reserves and exchanges for the whole world is too much for one country and one currency to bear."

Henry H. FowlerIncreasingly, the IMF and the international community realized that the Bretton Woods system - based on the gold standard and using dollars as the main reserve currency - had a serious flaw. The postwar "dollar gap" abroad had become a "dollar glut" by 1960.

U.S. Secretary of the Treasury

Liquidity and Deficit

Continuous U.S. balance of payments deficits during the 1950s had provided the world with liquidity, but had also caused dollar reserves to build up in the central banks of Europe and Japan. As the central banks redeemed these dollars for gold, the U.S. gold reserves dipped dangerously low.

How could the threatened system be fixed?

If there were too many dollars out there, why didn't the United States simply stop spending so much abroad?

The United States enjoyed the benefits of being able to spend money freely, such as acquiring commodities and consumer products from abroad. In addition, the U.S. foreign-policy goal of containing Communism in the face of the Cold War and decolonization kept the dollars flowing.

Triffin's Dilemma

Testifying before the U.S. Congress in 1960, economist Robert Triffin exposed a fundamental problem in the international monetary system.

If the United States stopped running balance of payments deficits, the international community would lose its largest source of additions to reserves. The resulting shortage of liquidity could pull the world economy into a contractionary spiral, leading to instability.

If U.S. deficits continued, a steady stream of dollars would continue to fuel world economic growth. However, excessive U.S. deficits (dollar glut) would erode confidence in the value of the U.S. dollar. Without confidence in the dollar, it would no longer be accepted as the world's reserve currency. The fixed exchange rate system could break down, leading to instability.

Triffin's Solution

Triffin proposed the creation of new reserve units. These units would not depend on gold or currencies, but would add to the world's total liquidity. Creating such a new reserve would allow the United States to reduce its balance of payments deficits, while still allowing for global economic expansion.

"A fundamental reform of the international monetary system has long been overdue. Its necessity and urgency are further highlighted today by the imminent threat to the once mighty U.S. dollar."

Robert TriffinThe Incredible Shrinking Gold Supply

November 1960

While the total number of U.S. dollars circulating in the United States and abroad steadily grew, the U.S. gold reserves backing those dollars steadily dwindled. International financial leaders suspected that the United States would be forced either to devalue the dollar or stop redeeming dollars for gold.

The dollar problem was particularly troubling because of the mounting number of dollars held by foreign central banks and governments:

- In 1966, foreign central banks and governments held over 14 billion U.S. dollars. The United States had $13.2 billion in gold reserves, but only $3.2 billion of that was available to cover foreign dollar holdings. The rest was needed to cover domestic holdings.

If governments and foreign central banks tried to convert even a quarter of their holdings at one time, the United States would not be able to honor its obligations.

Searching for Solutions

In the early 1960s, the world searched for ways to remedy the flawed Bretton Woods system of a fixed dollar-gold exchange rate:

- Western Europe and the United States cooperated to try to support the price of gold in the face of strains caused by speculators and hoarders.

- The United States adopted policies aimed at slowing the flow of dollars abroad.

- The IMF focused on adding liquidity without relying on gold or dollars. A new reserve asset, the SDR, was created to increase the total world money supply.

Could these efforts save the Bretton Woods international monetary system, or were its flaws so fundamental that a complete overhaul was needed?

The International Response

Europe and the United States Cooperate: The Gold Pool

In 1961, Belgium, France, West Germany, Italy, Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United States, and the United Kingdom agreed to contribute gold to a fund that could be used to support the price of gold at $35 per ounce, as decided at Bretton Woods. Gold could be sold from the pool if high demand threatened to raise its price on the open market.

The End of the Gold Pool

After 1966, dramatic increases in private gold buying by hoarders, speculators, and industrial users exhausted the gold pool supply. Member countries were forced to dip into their own gold reserves to meet the demand.

A rush to purchase gold from November 1967 to March 1968 finally caused the pool to disband.

The American Response

Decreasing the Dollar Drain

Alarmed at the flow of dollars abroad, the United States enacted policies designed to stem the flood.

- Tied Aid: More aid dollars were required to be spent on U.S. exports. In 1960, less than half of U.S. laid money was spent on U.S. products and services. By the mid-1960s, the proportion was close to 90%.

- Interest Equalization Taxes: Special taxes passed in 1963 and 1964 made it more expensive for non-U.S. citizens to buy U.S. stocks and bonds or borrow U.S. dollars.

- Voluntary Capital Control Program: In 1965, President Johnson launched a program to discourage U.S. corporate investing and spending abroad.

Initially, these and other efforts helped reduce the U.S. balance of payments deficit. In 1965, it reached its lowest level since the 1950s.

U.S. Policy Failure

The balance of payments deficit continued, despite government efforts to eliminate it.

- U.S. military spending abroad soared due to new involvement in Vietnam and continuing NATO responsibilities.

- U.S. tourists were spending several billion more dollars abroad than foreign tourists spent in the United States.

- U.S. private investment abroad continued to grow. Income from previous investment abroad continued to grow. Income from previous investments provided a substantial dollar inflow, but not enough to offset the overall balance of payments deficit.

- The U.S. trade surplus was rapidly diminishing, finally becoming a deficit in 1971.

The IMF Response

The Debate

Beginning in 1963, discussions on how to solve the international liquidity problem took place within the IMF and among its member nations.

- Some countries, such as France, wanted to set up additional international credit with strict rules for its use and payment - but continue to rely on gold as the main reserve asset.

- Others, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, wanted to create a new reserve unit to be used as freely as gold or the reserve currencies.

Which countries would receive the new reserve unit?

- The leading industrial countries favored a limited participation.

- The IMF and developing countries advocated giving all members - industrial and developing - a proportional amount of the new reserve unit.

The Decision

The Special Drawing Right (SDR) that was finally adopted in 1968 represented a compromise. It was essentially a new reserve unit, rather than additional credit, but because of certain restrictions, it could not be used as freely as gold.

SDRs were to be allocated to all participating IMF members, according to the size of their IMF quotas.

The SDR: Mixed Success

The additional liquidity provided by the SDR was quickly assimilated into the international monetary system. However, by the time the first SDRs were allocated in 1970, the world did not need more liquidity, since the United States had not reduced its balance of payments deficit. In fact, precisely in 1970-72, a big jump in the U.S. deficit caused a tenfold increase in members’ currency reserves. The SDR was designed to offset a dollar shortage that never materialized.

"...the first creation of international paper money, literally out of thin air."

The Economist, 1970Problem Persists

Flight from the Dollar

The efforts to mend the Bretton Woods exchange-rate system were no match for the severe exchange-rate crises of the late 1960s. Continual balance of payments deficits finally forced Britain to devalue the pound in 1967. People speculated that the dollar might soon follow. Private holders rushed to exchange their dollars for gold.

As a result, in 1968, the United States stopped redeeming privately held dollars for gold. Only central banks could still redeem their dollars at the fixed rate of $35 per ounce. Unable to get gold, private holders now sold their dollars for stronger currencies, such as the German mark, the Japanese yen, the Swiss franc, and the Dutch guilder.

For a time, many central banks, particularly the West German Bundesbank and the Bank of Japan, bought dollars to defend the U.S. currency and keep their own currencies from appreciating. This ended in May 1971, when the central banks began to redeem their dollar reserves for ever greater quantities of U.S. gold.

U.S. gold reserves were vanishing. If dollar redemption continued, they would soon be gone!

Bretton Woods System Collapses

On August 15, 1971, the United States stunned the world by declaring that it would cease redeeming dollars for gold from its reserves. With this, the dollar's link to gold was severed, dismantling the foundation of Bretton Woods. The financial system that had helped bring a quarter century of prosperity to the industrial world had finally collapsed.

With nothing concrete backing the U.S. dollar, would the world lose confidence in it? What would replace the Bretton Woods system?

By International Monetary Fund

Source: International Monetary Fund

alloyed gold

No comments:

Post a Comment

I thank for the comment!