The Affordable Care Act will open doors for more patients to get treatment, but resources may not be there to meet the demand in states such as Delaware.

Tricia Hill gave up trying to get health insurance years ago.

The 39-year-old Newark resident spent two decades in the throes of a chronic mental health disorder, a condition that made it hard for her to hold a job and easy for insurance companies to reject her applications for coverage.

"It seemed like it was hopeless," said Hill, who declined to detail her condition.

So she relied on disability benefits.

That's about to change dramatically for Hill and thousands of other Delaware residents, as the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, makes it illegal for those with pre-existing conditions to be rejected for coverage -- and mandates mental health care coverage starting in 2014.

But just because you'll be entitled to the services doesn't mean you'll get an appointment -- at least not a quick one in Delaware, which has a shortage of mental health practitioners, according to the U.S. Health Resources and Services Association.

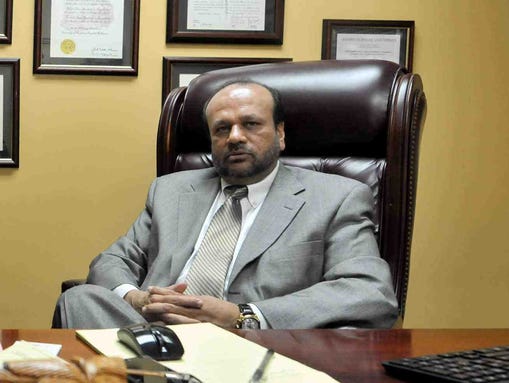

"There is no way we can serve all of them," said Dr. Ranga Ram, a psychiatrist in Brandywine Hundred, who expects far more emerging patients than the system can absorb, with some estimates putting the number at 30,000. "The hope is that they will stagger in over a period of three or four years."

The number of working psychiatrists in Delaware is hard to come by. The number who are accepting new patients is even more elusive. The state Division of Professional Regulation reports 113 licensed psychiatrists in the state, but some are retired and/or not accepting new patients.

New avenues will have to open, Ram said -- for therapists, advanced practice registered nurses and others -- and more collaboration with primary care physicians will be needed.

But coverage starts in two months, and the gaps in the system will be enormous.

Effective treatment can have profound implications for those who need the care. When their condition is stabilized -- as Hill's now is -- they can get and keep better jobs, avoid medical problems triggered by unaddressed mental health conditions and avoid situations that lead to criminal charges and/or jail.

Over capacity

Federal officials estimate that one in four people with no insurance have mental health or substance abuse conditions. They expect 32 million new patients to seek care under the new law.

In Delaware, which has an estimated 90,000 uninsured residents, that would mean about 22,500 with potential need for care -- not counting those who already have some kind of medical insurance but none for mental health or substance abuse.

|

| Dr. Ranga Ram |

"We've had a pinch in supply and demand all the way along the line," said Dr. Michael Marcus, director of outpatient services in psychiatric and behavioral health for Christiana Care.

Christiana Care is expanding its approach to mental health care, and the state has been aggressive in its expansion of community-based care to comply with requirements of a 2011 settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice.

The Department of Justice settlement is an important part of the context, because its 2009 investigation found that the "vast majority" of patients at the Delaware Psychiatric Center should be living in the community, not in the state's largest psychiatric hospital. The state is required to make sweeping reforms to support community-based care.

A growing network of service and support is emerging statewide -- crisis services, drop-in centers, peer supports and mental health services.

Still, according to 2012 data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, only about 39 percent of the state's need is met at current levels.

"We have under-supply and a mismatch in distribution," Christiana's Marcus said. "Fortunately, we've had some lead time to work on this. We're hiring behavioral health care professionals on an ongoing basis and we're in close consultation with state officials to coordinate our plans. … We have to step up all of our games."

To address more severe shortages in rural areas, Lewes-based Beebe Healthcare now has a partnership with In-Sight Telepsychiatry, offering its staff video consults with psychiatric specialists. That capacity is available in the emergency department and on the hospital floors, according to Beebe spokeswoman Sue Towers.

In addition to Beebe, In-Sight is providing telepsychiatry services to Kent-Sussex Counseling in Dover and Crossroads of Delaware in Wilmington, and recently established a partnership with Resources for Human Development (RHD) for its programs in New Castle and Kent counties, said In-Sight account executive Dan Khebzou.

Marcus said another good expansion strategy is the use of "physician extenders" -- advanced practice registered nurses, for example -- who can assist with evaluations and medications.

But the best strategy is finding ways to integrate mental and medical care, Marcus said.

"Behavioral health care and medical-surgical services have been somewhat siloed," he said. "It's not just more treatment that is needed, but treatment that will improve people's health care," he said. "We have to really keep adding capacity and in a smart way. … So it's not necessarily more of the same, but in a more innovative way."

Christiana Care's decision to embed a psychiatrist in its cardiac center is an example, Marcus said. A person with an undiagnosed anxiety disorder may arrive at the hospital in a full panic attack, with symptoms indistinguishable from cardiac distress, he said. They would get a full cardiac "workup" to find out what's going on medically, Marcus said.

Having a psychiatrist available for a mental health consultation makes it possible to diagnose psychiatric problemswith greater accuracy and treat the patient more effectively.

Removing barriers

The Affordable Care Act removes several artificial barriers to care, psychiatrists Marcus and Ram said. Refusal to cover those with mental health problems will be illegal, and some limits to care have been removed, too. A 20-visit cap on therapy sessions, for example, will be gone, though Linda Nemes of the Delaware Insurance Commissioner's office says all care will be reviewed and managed as it unfolds.

Nemes said health insurance issuers Highmark and Coventry were required to certify an adequate network of providers to gain the marketplace contracts in Delaware. The state will monitor performance to be sure those requirements are met, she said.

The new coverage may open new doors for Hill, who is working part-time as a peer specialist to help others with mental health conditions gain traction in their recovery. Under present rules, she can't take on additional responsibilities or get a full-time job because she must keep her monthly income at or below $1,040 or lose her disability benefits.

If she can get the health care she needs through the Affordable Care Act, she may be able to live her dream -- finish her college degree, get a master's, and become a full-time social worker.

"I've made a lot of progress," she said. "I was at a point where I was completely unable to function without a lot of care. I received a lot of assistance. Now, I'm at the point where I have almost no assistance.

"I've come a really long way. I decided to take personal responsibility for my own recovery and started working toward making that happen."

By Beth Miller, The (Wilmington, Del.) News Journal

Source: The USA Today

No comments:

Post a Comment

I thank for the comment!